What was the church’s reaction to this crisis? Unfortunately, at that time the church was often perceived to be part of the problem. Many congregations were still in denial that their members were dying from AIDS, and some believed that AIDS was a judgement from God.

Yet the last decade has seen amazing progress in the response to HIV and AIDS. The rate of HIV infections and deaths is slowing down, and world leaders are now trying to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030. What has caused this transformation?

The world wakes up

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been available since the 1990s, but at first it was incredibly expensive, costing more than 10,000 USD each year for one person. Campaigns such as the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) of South Africa were very successful in making ART much more affordable (see page 22 for more details).

The next important breakthrough was in July 2005 when the leaders of eight high-income countries (known as the G8) met at Gleneagles, Scotland. Influenced by a powerful advocacy campaign, the leaders agreed to work towards universal access to HIV prevention, treatment, care and support. They also made commitments to provide funding to achieve this goal.

After this meeting, the number of people receiving ART steadily increased. In 2005, fewer than 2 million people were receiving effective treatment. By March 2015, this number had grown to 15 million.

As a result of effective treatment, HIV-positive people are now living longer. The disease is no longer considered to be a ‘death sentence’, but instead has become a manageable long-term illness. With good treatment, HIV-positive people can now have a similar lifespan to people who do not have HIV.

Steps forward in prevention

When people first started trying to prevent the spread of HIV, the ABC approach was popular (abstain from sexual activity, be faithful, use a condom). However, this way of thinking was too narrow. The organisation INERELA+ developed the SAVE approach (Safer practices, Access to treatment, Voluntary counselling and testing, and Empowerment) to be more holistic, while still including the ABC principles (see page 19 for more details).

In 2007 a new prevention method was recommended by UNAIDS and the World Health Organization (WHO) – voluntary male circumcision. This reduces the risk to men of contracting HIV through heterosexual intercourse (although it only partially lowers the risk, so other methods of protection must also be used). Between 2007 and 2013, around 6 million men were newly circumcised in 14 countries in East and Southern Africa with a high prevalence of HIV.

Further progress in treatment

It was well known that ART could save lives. But in 2011, an important piece of research showed that effective ART could also help to prevent the transmission of HIV from one person to another. This is because ART can reduce the amount of HIV present in a person’s body (known as their ‘viral load’), to the point where it cannot be detected in a blood test. When a person’s viral load is this low, their risk of transmitting HIV to another person is greatly reduced (though they should still take other precautions).

Another development in HIV prevention was pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). This is a special type of daily medication that can help to prevent people from becoming infected with HIV. It is intended for those who are at high risk of exposure to HIV (such as sex workers or people who inject drugs). Other protection methods must also be used, as it is not 100 per cent effective in preventing HIV from being passed on.

Preventing mother-to-child transmission

There has been great progress in preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In 2011 the ‘Global Plan’ was launched, which aimed to stop children becoming infected with HIV and to protect the health of mothers. Without any health care interventions, a pregnant woman who is living with HIV has up to a 45 per cent chance of passing HIV on to her baby. However, with proper treatment, this risk can be reduced to below 5 per cent. In 2013 WHO recommended that all pregnant and breastfeeding women with HIV should be provided with ART.

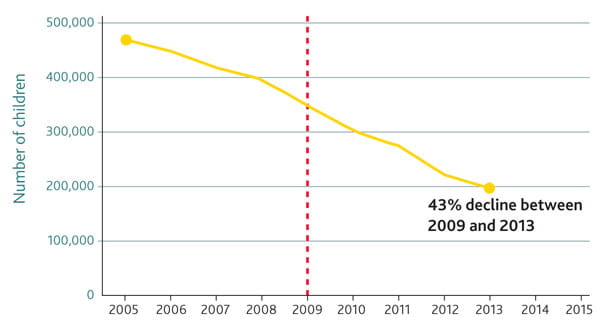

The Global Plan focused on the 22 countries with the highest number of pregnant women living with HIV. Between 2009 and 2013 there was a remarkable 43 per cent decrease in the number of new HIV cases in children in 21 of these countries.