For people who rely on rain-fed agriculture, land degradation and the loss of soil fertility can be devastating. Farmer-managed natural regeneration uses simple, low-cost techniques to encourage the regrowth of trees from live stumps and from seeds in the ground. This results in the restoration of land and livelihoods.

The skills associated with this practice have been used for generations. However, in the early-1980s they were revised and made popular again in response to serious land degradation in Niger. Vast areas of deforested land had become badly eroded resulting in failed crops and chronic hunger.

Attempts to plant trees and restore soil fertility had often failed because of extreme heat, limited water, freely grazing livestock and lack of interest. Most farmers did not understand the benefits of trees and were preoccupied with trying to meet their immediate needs. A new approach was required: one that would empower farmers to restore their land, while at the same time improving agricultural production.

Living stumps

Instead of planting trees, farmer-managed natural regeneration relies on regrowth from live stumps, roots and seeds already present in the soil: the underground forest. The living stumps of previously felled trees have mature roots that are able to reach nutrients and water deep in the ground. These roots also release stored energy as new shoots grow. This means that regrowth is usually faster, and more successful, than the growth of newly planted seedlings.

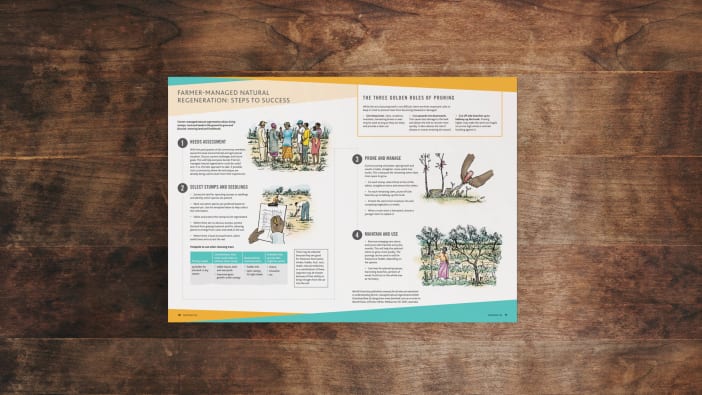

Often in agricultural fields, tree regrowth is cut or burnt before each crop-planting season. With farmer-managed natural regeneration, as regrowth emerges the strongest, straightest stems are protected and the other stems are cut off. Land users decide which trees to keep, depending on the type of tree they want to grow and the location of the stumps. The basic techniques are easily learnt and passed on from farmer to farmer.

Animals are kept away from the regrowth until the young trees have grown to a point where grazing won’t harm them any more. After that, livestock can be allowed to graze around the trees, fertilising the soil in the process.

The crop growing season can be a good time to regenerate trees because livestock is often penned or grazed elsewhere. On communal land, communities must decide together how best to keep animals away from young, vulnerable trees.

Trees on farms

Deliberately including and managing trees and shrubs on farmland has been shown to have many benefits. These include:

- reduced soil erosion because of deep roots and permanent soil cover

- improved soil structure and fertility

- better retention of rainwater in the soil and reduced risk of flooding

- cooler soil making it easier for crops and grass to survive hot, dry spells

- habitat for a variety of wildlife, including insects and birds important for pollination and pest control

- lower wind speeds and less airborne dust

- cooling shade for humans and animals.

Different tree species can provide firewood, timber, natural medicines, fodder and food. Enterprises such as bee‑keeping can also be developed. Some tree species – called legumes – take nitrogen from the air and add it to the soil. Others draw water up towards the surface, making it available for crops to use.

Flexibility

Farmers and land users can practise farmer-managed natural regeneration in a number of different ways. They have the freedom to choose which trees they want to conserve, and when and how to prune. The result can be as simple as growing a few trees for firewood, or the techniques can be used to restore large areas of forest.

When the land is individually owned, tree regeneration is best managed by the land user or owner. On communal land, the whole community should be involved. This ensures that everyone understands the importance of looking after the trees, and everyone shares the benefits.

Many benefits

In Niger, farmer-managed natural regeneration has grown to cover more than 5 million hectares. As the land has become green with trees, crop yields have increased benefiting 2.5 million people. In 2005, when a third of Niger’s population suffered from famine, sale of firewood and other forest products meant that farmers practising natural regeneration were able to avoid tragedy and did not need to rely on famine relief.

Typically, farmer-managed natural regeneration costs about 40 USD per hectare to implement. However, once introduced, the cost is only that of the land user’s labour which in Niger is around 14 USD per hectare. After 20 years, farmers in Niger were growing an extra 500,000 tons of grain every year and annual incomes rose by up to 1,000 USD per household. By comparison, a study of three West African countries found that 160 million dollars had been spent on tree planting and only about 20,000 hectares of plantations remained: a cost of 8,000 USD per hectare.

Commitment

Success is most likely if there is a high level of commitment. Many farmers feel that the presence of trees on their land is unhelpful. However, as understanding increases, so does the desire to grow trees. If most people in a community are working towards achieving the same goals, greater progress will be made.

For more information about how to practise farmer-managed natural regeneration, download this poster.

World Vision has published a comprehensive manual on all aspects of farmer-managed natural regeneration. Download free of charge from www.fmnrhub.com.au.