Policy positions

Designing sustainable subsidies to accelerate universal energy access

Key principles for the design of pro-poor subsidies to meet the goal of sustainable energy for all

2020 Available in English

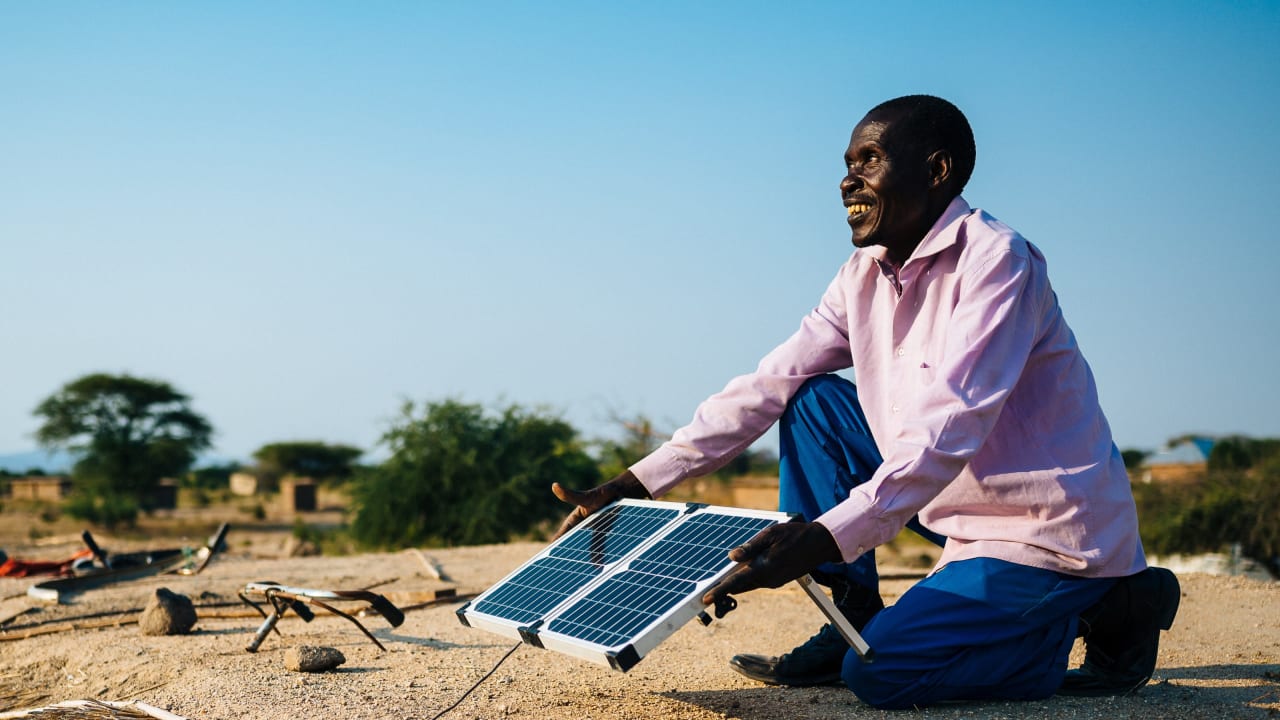

Man positions a solar panel on the roof of his house in Tanzania. Photo: Tom Price/Tearfund

Download resource

Similarly Tagged Content

Share this resource

If you found this resource useful, please share it with others so they can benefit too.

Get our email updates

Be the first to hear about our latest learning and resources

Sign up now - Get our email updates