Sitting under a mango tree with a small group of Ugandan farmers eight years ago, I thought I had found the perfect placement as a volunteer. We would discuss the relative benefits of chili pepper and onions as insect repellents one week and various designs of fuel-saving stoves the next. Working for a small NGO (non-governmental organisation), talking to farmers every day, using participatory methods to help them find solutions to their problems, and seeing small improvements week by week, was an experience I’ll never forget.

But I soon realised two things:

- there was a huge demand for this kind of basic knowledge

- this demand was never going to be met by teaching small groups of farmers under mango trees.

I needed teaching materials to help these messages reach a bigger audience, and to enable farmers to teach themselves. But all I found were lengthy black and white textbooks with too few illustrations and too much technical language. Teaching materials seemed to be designed more for scientists than for farmers.

Since arriving in Uganda, I had been impressed by the educational campaigns about HIV. On the roadside, there were colourful billboards showing condoms, and in bars and restaurants there were posters about faithfulness and abstinence. You could see how the country had become a success story by halving HIV prevalence in ten years.

I began to wonder why agriculture and livelihoods were not getting the same attention as HIV and the health sector. Why were there no billboards about growing fruits and vegetables? Why were there no posters about making compost and mulching? And that was the moment I realised I wanted to try to do for agriculture what had already been done for HIV.

The design process

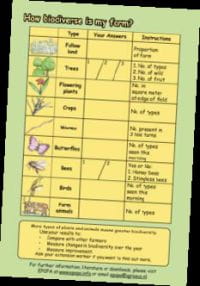

I set up Fourthway in 2004 to publish teaching materials for farmers that were the same standard as those in the health sector. The original idea was to design materials demonstrating simple techniques to improve yields that would cost farmers nothing. The first prototypes (draft versions) showed how to make compost, liquid manure, and simple organic pesticides. They were designed with lots of pictures and few words to make them easy to understand.

We took our rough prototypes around some local Ugandan NGOs. Their first reaction was one of surprise: ‘We’ve never seen anything like this before, but I can already tell you we need these a lot,’ said one. ‘You mean we’re allowed to suggest changes?’ said another. It sometimes took a while to explain that we wanted to develop materials in participation with the NGOs.

Working with NGOs gave us practical and technical expertise. Extension workers also made the following suggestions:

- make posters instead of books – things that can be pinned up and be seen everywhere

- make them look modern, to challenge the idea that agriculture is old-fashioned.

Further development with farmers helped us to simplify instructions. They told us to include photos and quotations to show how the posters were rooted in real-life practice.

Since 2004, this cycle of development has continued. We produce prototypes, test them with extension workers, and then with farmers. We have produced hundreds of thousands of posters around East Africa for government and NGOs. Mass production has enabled us to keep costs down. Five years on, some health-related organisations are coming to look at agriculture for new ideas in design.