Fair trials have special protections that make sure everybody accused of a crime gets treated fairly, or justly, within the criminal justice system.

Articles

What makes a fair trial?

What are the key elements of fair trials, and what can you do if these are not happening in your country?

Written by Sabrina Mahtani and Jennifer Riddell 2018 Available in French, English, Russian and Spanish

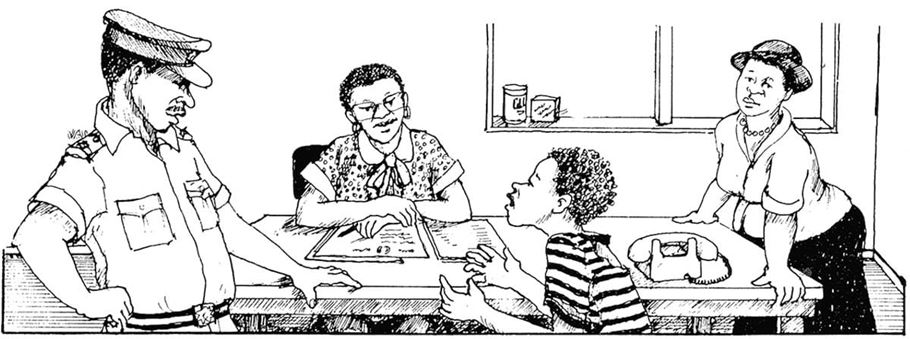

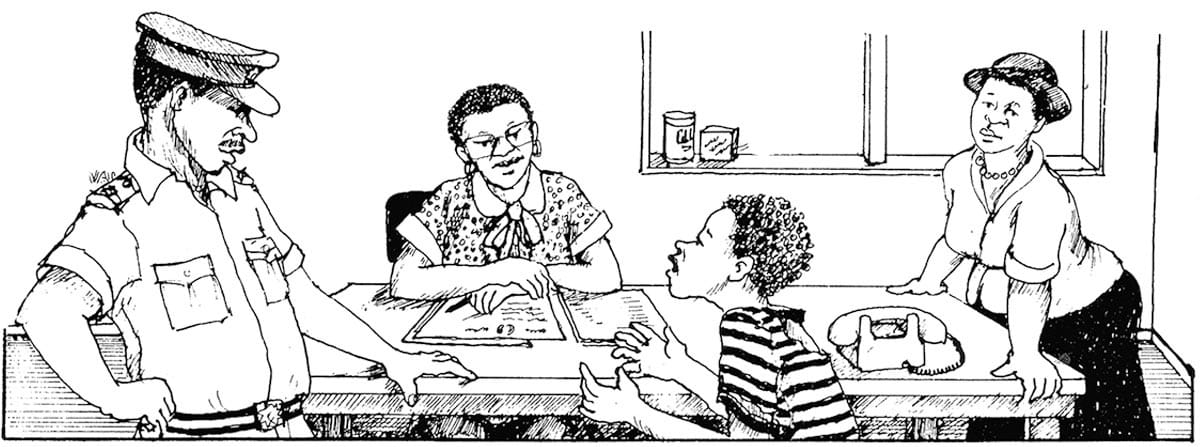

AdvocAid’s paralegal Nenny provides legal aid and practical help to female prisoners. Photo: AdvocAid

From: Prisons – Footsteps 104

Practical tips for getting involved in prison ministry and caring for ex-offenders

Illustration from Petra Röhr-Rouendaal, Where there is no artist (second edition)

Why are fair trials important?

Fair trials are critically important in every country. They ensure that governments cannot convict someone or take away their liberty without following fair and just processes. They make sure that anyone accused of a crime can understand what is happening to them. Fair trials ensure that people can trust and have confidence in the criminal justice system in their country.

The right to a fair trial is included in many constitutions around the world. It is a central foundation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948. Though individual countries will have varying rules and procedures, below are some basic principles about what makes a fair trial:

- the right to information about the situation

- the right to a lawyer

- the right to be heard by a competent, independent and unbiased tribunal

- the right to a public hearing

- the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty

- the exclusion of evidence obtained in a way that breaks international standards (eg through torture)

- the right to have adequate time and facilities to prepare a defence, and the right to be heard within a reasonable time

- the right to be present at trial

- the right to call and examine witnesses

- the right to an interpreter and translation, if necessary

- the right to appeal a conviction and sentence

What are the challenges?

In many countries, fair trials do not always happen. Reasons for this include weaknesses in the legal system, such as insufficient or poorly trained judges and lawyers. Many people lack an awareness of their rights. Another big challenge is corruption. Corruption can be found at all levels, from the court administrative officers, who may decide which case is heard next, right up to an appeal court judge.

Helping achieve fair trials

1. The first step is to know what your rights are. Then you can try and claim them, and can share this knowledge with others.

2. Get information about lawyers or legal aid NGOs that you can contact if you need assistance. Some may offer legal rights training.

3. Be aware of the individuals and organisations in your country to which you can report violations of fair trial rights. These include the Human Rights Commission and the ombudsman (an official who investigates people’s complaints against public officials and institutions).

4. Be aware of international bodies that you can contact about violations of fair trial rights (eg UN Special Rapporteurs).

5. Ask your government representatives to do more to ensure fair trial rights (eg more funding for courts, police and legal aid).

To read a longer version of this article, visit www.tearfund.org/fairtrial

CASE STUDY: From death row to freedom

In 2003, ‘MK’ (name protected for her privacy) was arrested and held in Sierra Leone for the murder of her step-daughter.

The truth was that MK’s husband had accidentally sat on the six-month-old baby, suffocating it. They were both arrested, and he told the police that she had poisoned the baby with battery fluid. They believed him. He told MK to confess and that the matter would be resolved in a traditional family way. MK put her thumbprint on a confession (which she was not able to read), and this was later used against her in trial.

Between 2003 and the beginning of her trial in 2005, MK received no legal advice or assistance. It was only at the start of the trial that she was given a state defence lawyer. He was so busy that he had just three meetings with her of less than 15 minutes each. MK was illiterate, terrified and alone.

An unfair conviction

During MK’s trial she had no idea what was happening, as proceedings were conducted in English, a language she did not speak. She was found guilty of murder, sentenced to death and transferred to a maximum security prison.

Unable to read, write or pay for a lawyer, MK had to rely on the state-provided Prison Welfare Officer to file for appeal. This was not done properly or followed up. When she was convicted, no one informed her she had just 21 days to appeal. Furthermore, her file was not sent to the President’s office for further review, as required by law.

MK was imprisoned in a small, dirty cell in the overcrowded Pademba Road Prison. Shortly after her sentencing, the legal aid organisation AdvocAid met MK in one of their prison literacy classes. They took on her case and began the long process of trying to obtain her court file from the provinces. This took several months due to poor filing procedures.

Campaigning near and far

AdvocAid hired a lawyer, who filed an appeal before the Court of Appeal in 2008, but MK’s case was rejected due to being out of time. An old law in Sierra Leone says that extra time to appeal can be granted, but not in cases where a person was sentenced to death. MK was devastated when she heard this news.

AdvocAid did not give up, though. They drafted a policy paper called 21 Days: Enough Time to Save Your Neck? They also began lobbying various parts of the justice sector for reform. They requested support from senior Sierra Leonean lawyers, lawyers in the UK and the specialist UK NGO, The Death Penalty Project.

They also began a campaign with civil society organisations in Sierra Leone to have the women on death row pardoned, and intensified their lobbying against the death penalty. They wrote press releases sharing the stories of women on death row, spoke on numerous radio and TV programmes and asked the women’s movement to back the cause.

In November 2010, the Court of Appeal agreed to hear MK’s case. Arguments for reconsidering the case included the fact that MK’s husband, the primary witness, had never been cross-examined.

Persistence pays off

In March 2011, MK’s case was heard by the Court of Appeal. With dedicated legal support on her side, the case against MK quickly fell apart. The court agreed with the AdvocAid lawyer’s demonstration that the initial trial had been unfair. The judge overturned the earlier ruling, and the prosecution dropped its case against her.

On that day, MK was released from death row, six years after her sentencing and eight years after her imprisonment. She was the longest-serving woman on death row in Sierra Leone.

Discussion questions

- In what ways did MK’s case fail to meet the requirements for a fair trial?

- What could have helped prevent MK’s unfair conviction?

- What do you think made AdvocAid’s approach so effective?

- Do you know any other stories of unfair trials? Could you use any of the approaches described here to work towards more just outcomes?

View or download this resource

Get this resource

Get this resource

Written by

Written by Sabrina Mahtani and Jennifer Riddell

Sabrina Mahtani is the co-founder of AdvocAid, an organisation providing education, empowerment and access to justice for girls and women in Sierra Leone. Jennifer Riddell is a criminal lawyer based in England. Web: www.advocaidsl.org Email: [email protected]

Similarly Tagged Content

Share this resource

If you found this resource useful, please share it with others so they can benefit too.

Subscribe to Footsteps magazine

A free digital and print magazine for community development workers. Covering a diverse range of topics, it is published three times a year.

Sign up now - Subscribe to Footsteps magazine